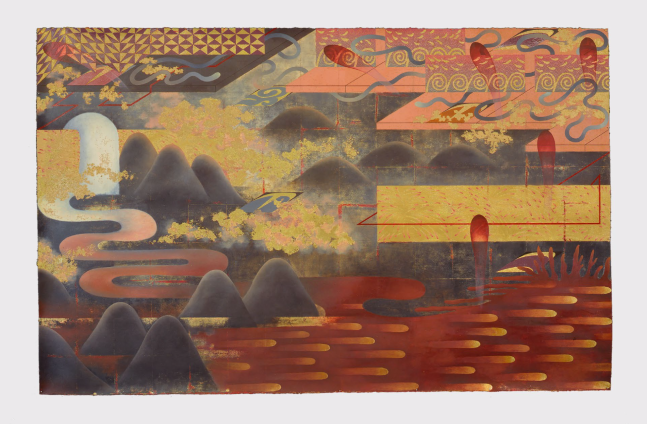

Takako Yamaguchi, Found, Lost and Then Found Again, 2004

Takako Yamaguchi is an artist and painter who has been based in Los Angeles since 1978. Moving between the United States, Japan and France in the early years of her practice, Yamaguchi developed a uniquely syncretic approach to art making well before the term “globalism” became commonplace. She has long been sensitive to the tension between an ostensibly race-neutral kind of International Modernism on the one hand, and the aesthetics of local, national and ethnic identity, on the other. Rebuffing the formal reductivism of European abstraction and the austerity of American Protestantism as simplifications of difference, Yamaguchi turned instead to what she once dubbed, “the trash-heap of discarded ideals.” There she focused her attention on such disfavored subjects as decoration, fashion and beauty, sentimentality, empathy and pleasure; a collection of forms and values she holds all the more dear for the ease with which they were displaced by modernity.

From the beginning, and intermittently over the course of her career, Yamaguchi has developed a repertoire of motifs sourced from her native Japan—images drawn from decorative screens, woodblock prints, kimono patterns, commercial graphic design—and deployed these in a manner she has dryly characterized as “self-orientalizing.” The artist’s “Japonisme,” so to speak, is further complicated by her engagement with other visual traditions intentionally outside of the current artistic zeitgeist, including European Romanticism, American Transcendentalism, Mexican Socialist murals, Art Nouveau, and Photorealism. Reveling in what has historically been deplored as fickle and superficial, and thus inevitably as feminine–as well as often racialized–the work manages to uncover commonalities between widely differing styles through Yamaguchi’s singular hand.

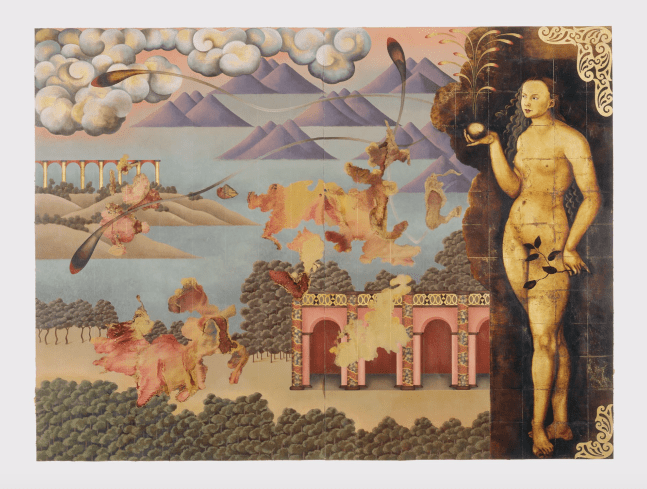

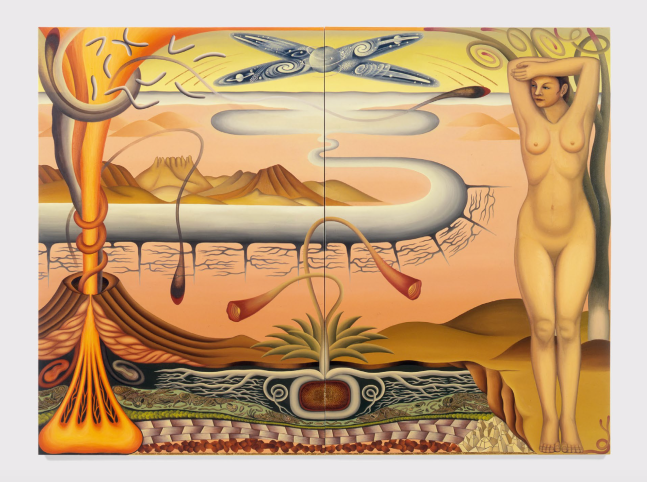

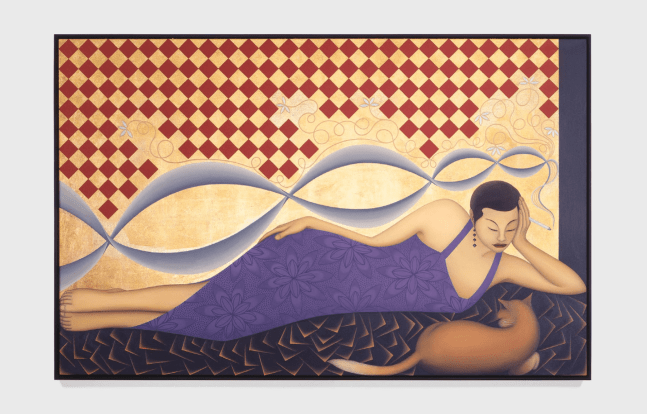

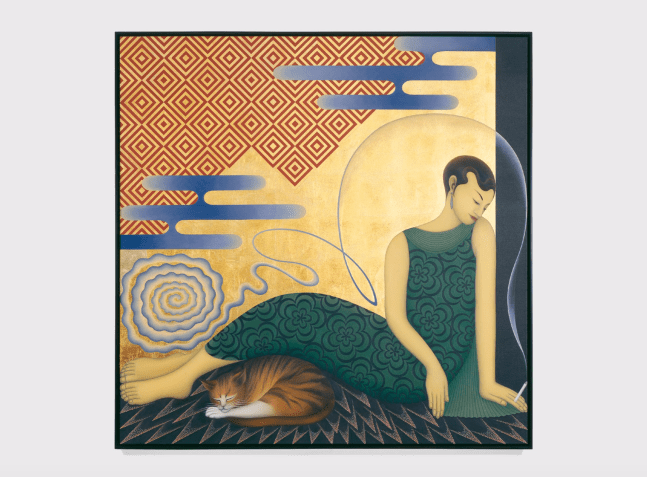

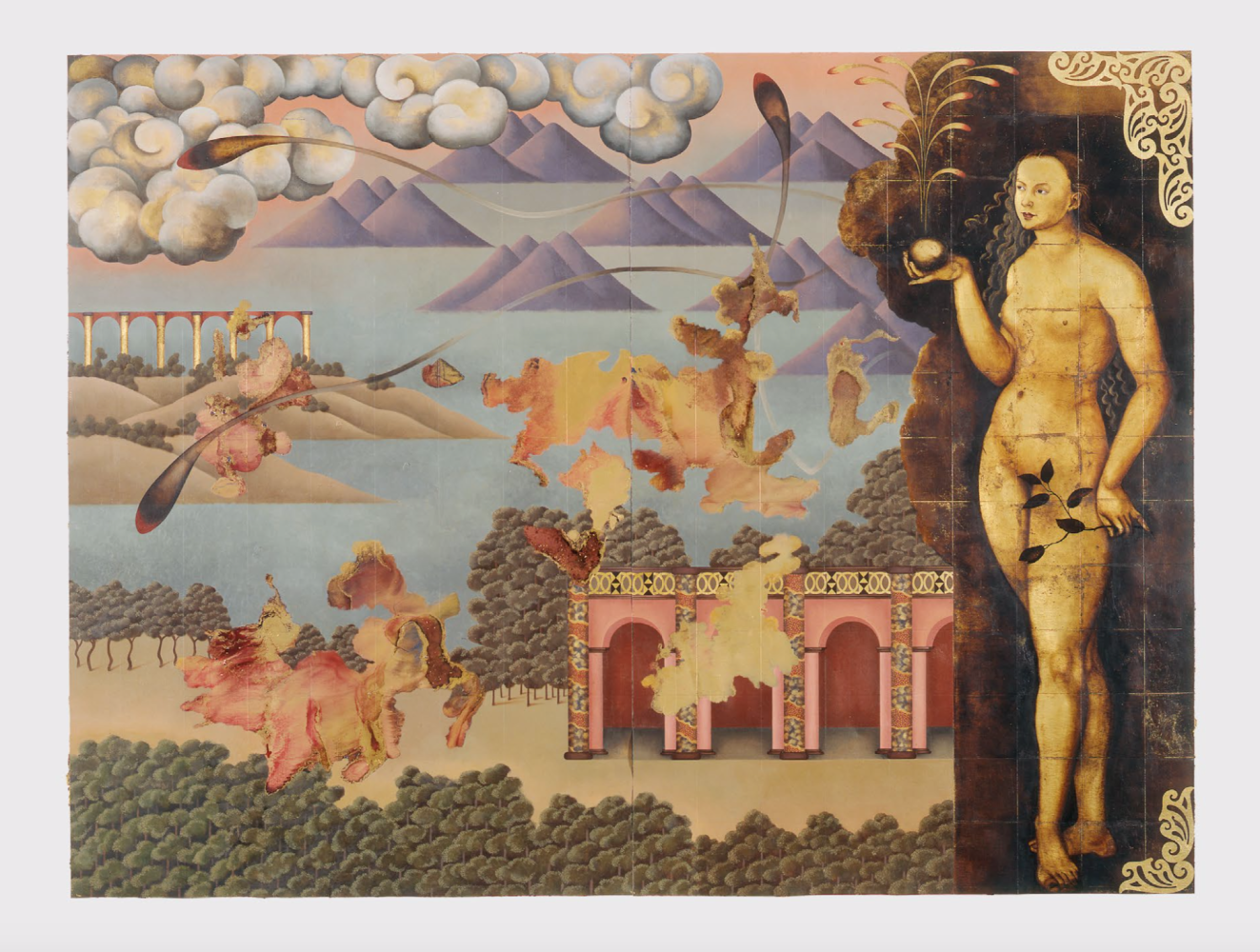

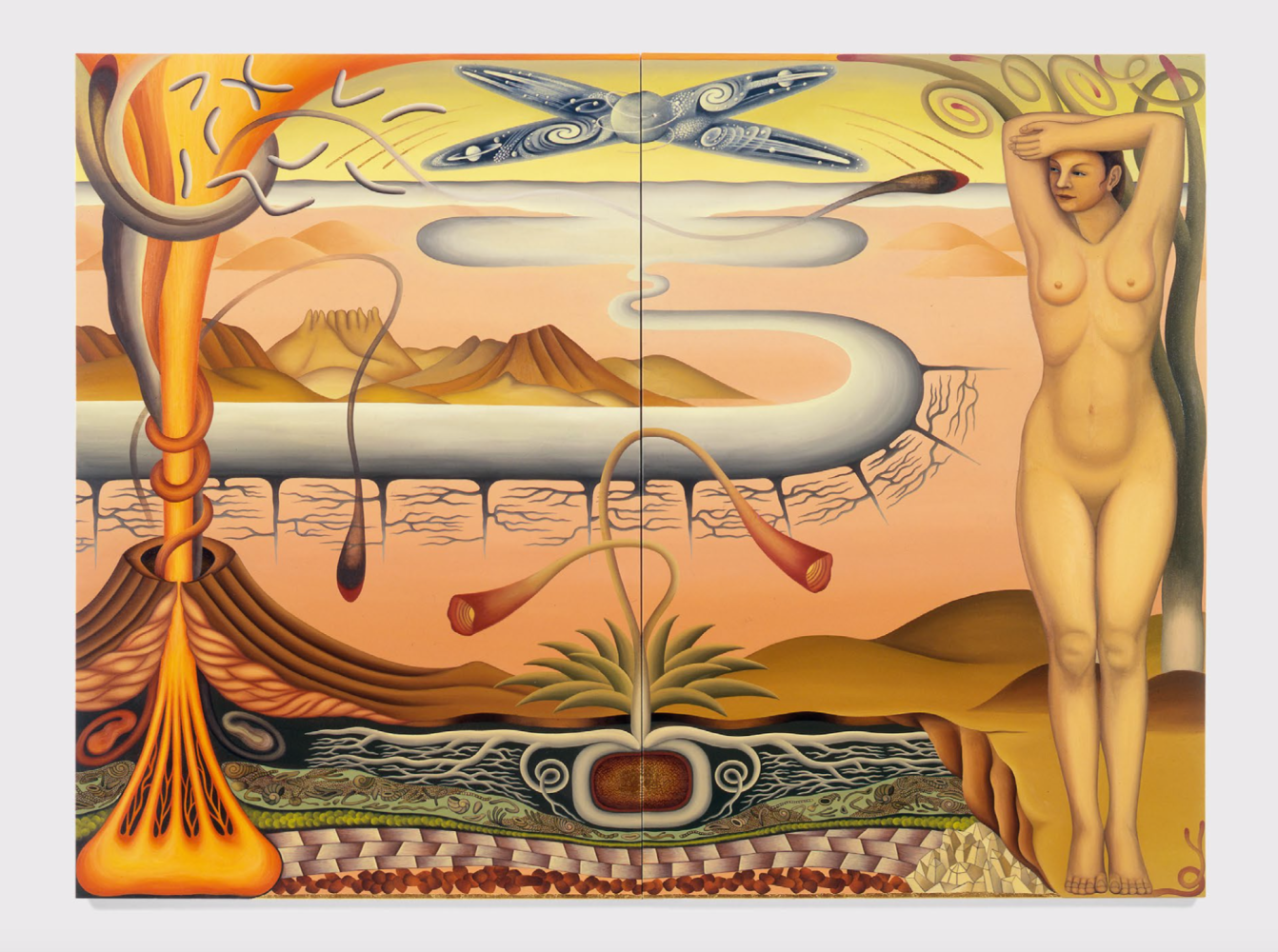

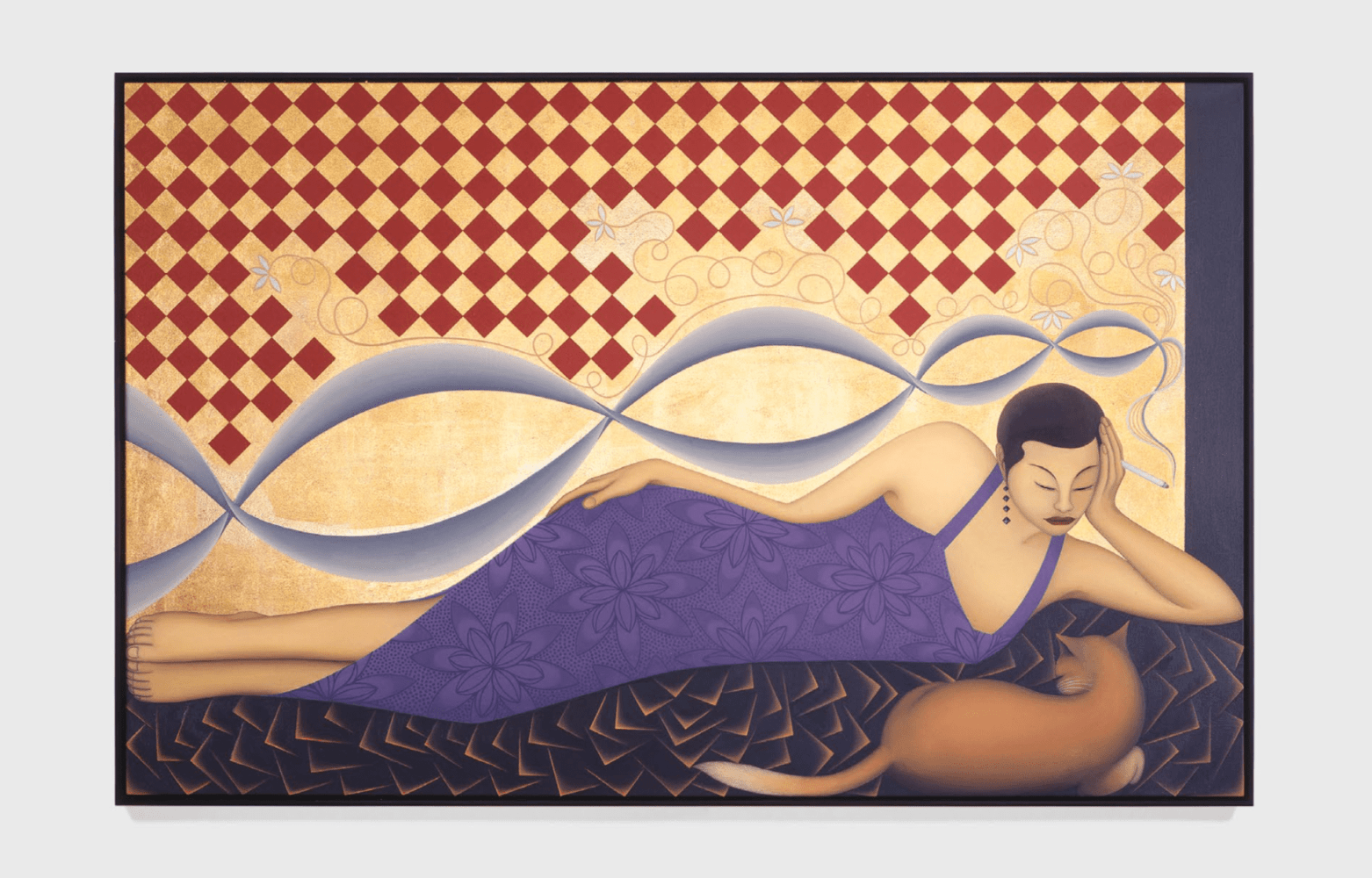

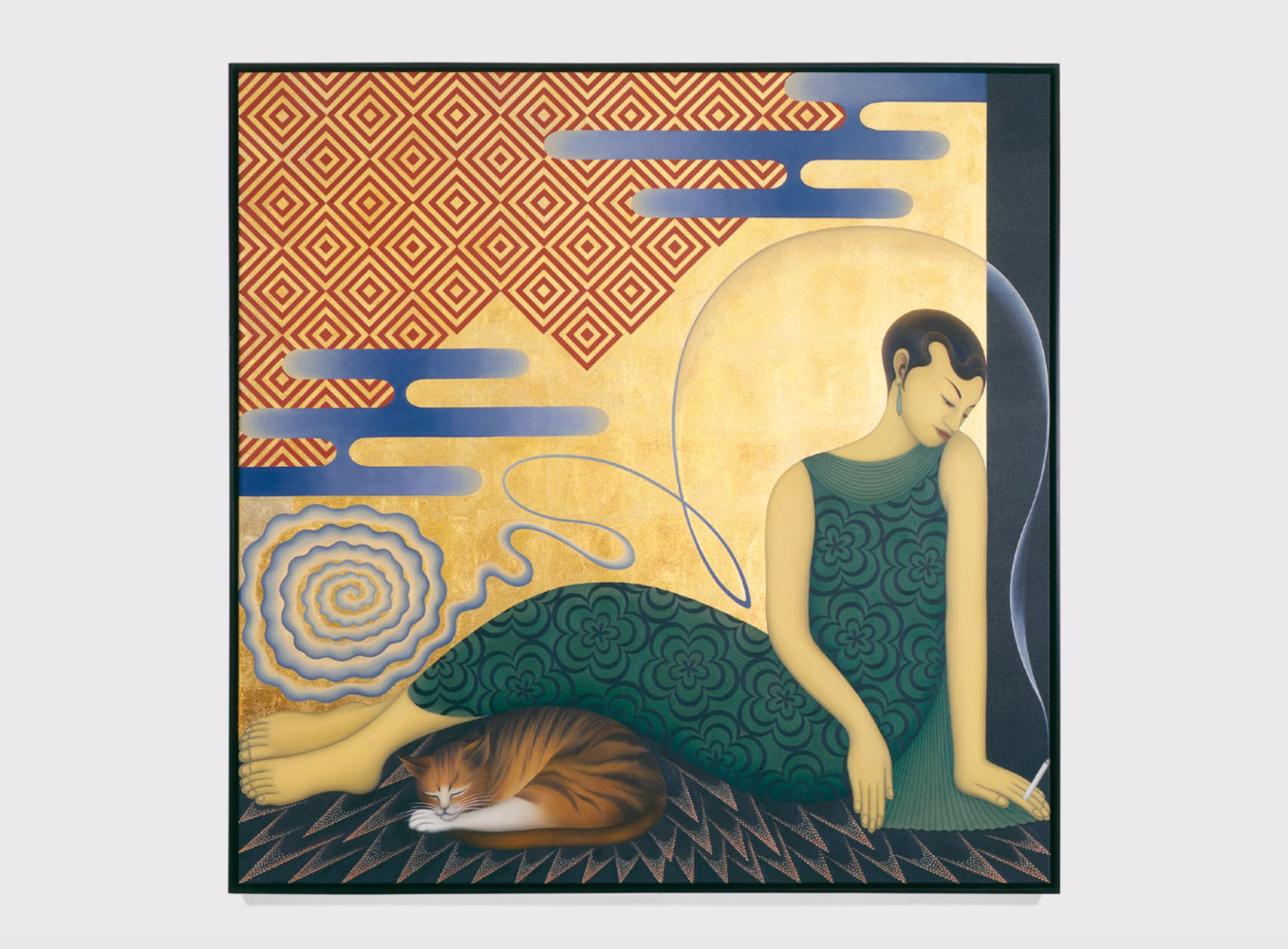

With an interest in recuperating the styles and histories abandoned by Modernism, Yamaguchi proposes a “poetics of resistance” where her own statement is ever-so-slightly out of step with prevailing taste and therefore only just barely legible at its moment of enunciation. Her Innocent Bystander series, for instance—executed in 1988 and 1989, just upon returning to Los Angeles after an extended stay abroad—inserted images of Eve borrowed from Lucas Cranach the Elder into a world of painterly flourishes derived from Western and Asian art history. Yamaguchi’s paintings in this series attempt to “recover” the ghost of a lost style, the kind of antiquated, nearly Victorian sensibility over which Modernism once so decisively triumphed. Subsequent paintings circle around the art of Diego Rivera from the 1920s and 1930s; a perhaps perverse choice for an artist of Asian ancestry but one which functions simultaneously as a love letter to an influential predecessor and as an indirect challenge to received notions of ethnic identity and the presumed ownership of culture. Yamaguchi followed these with a series of lavish portraits mining the fin-de-siecle decorative arts. Collectively titled, Smoking Woman, the paintings feature elaborate garments, feminine poses, pet cats, geometric patterns, cigarettes and cigarette smoke, combined together in an exquisitely subtle subversion of the expected politics of the culture wars that haunted the era.

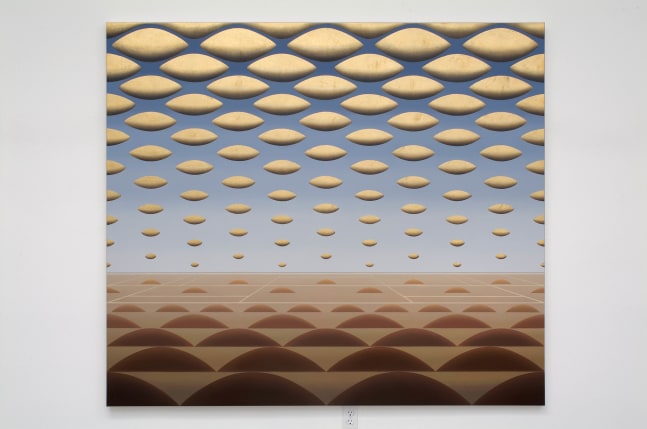

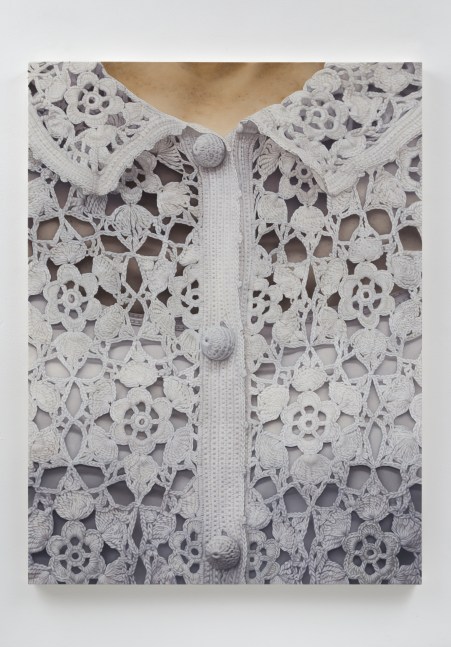

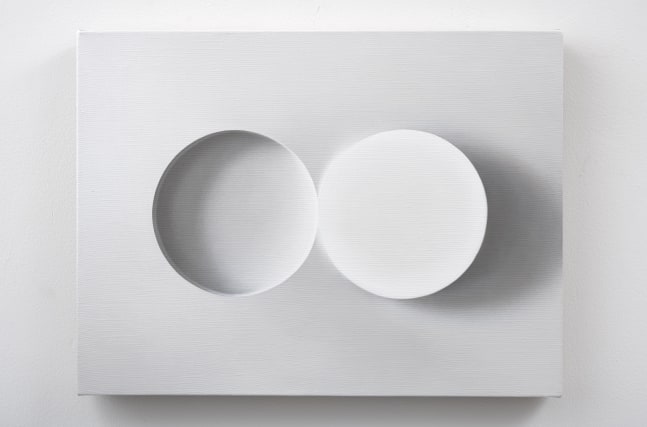

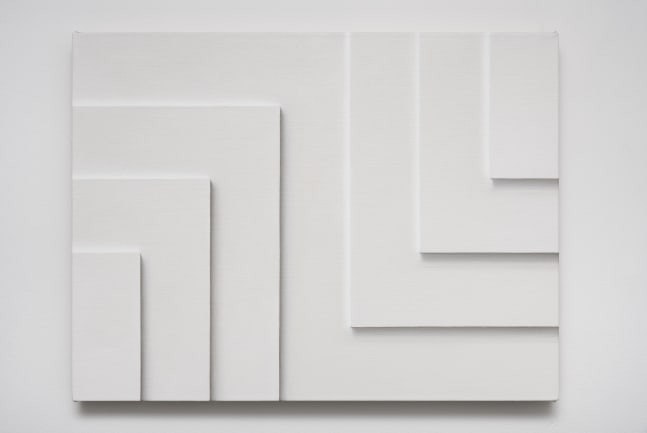

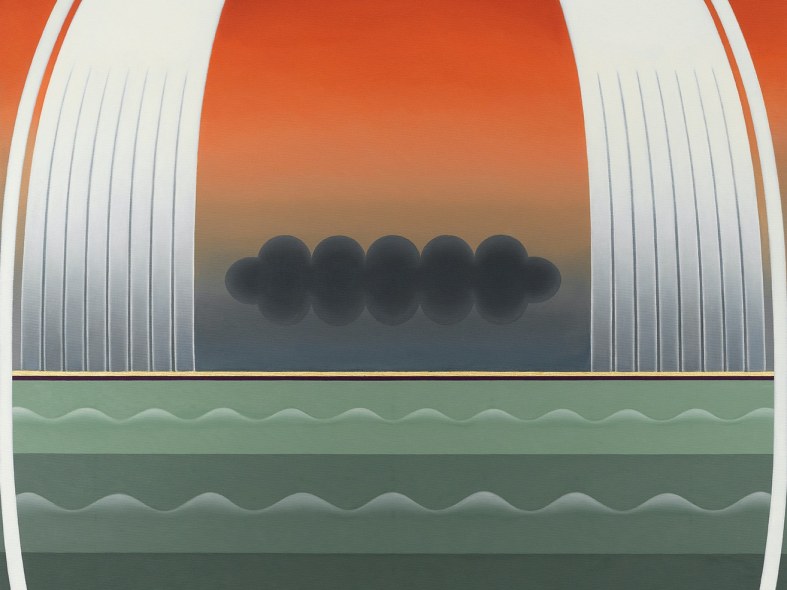

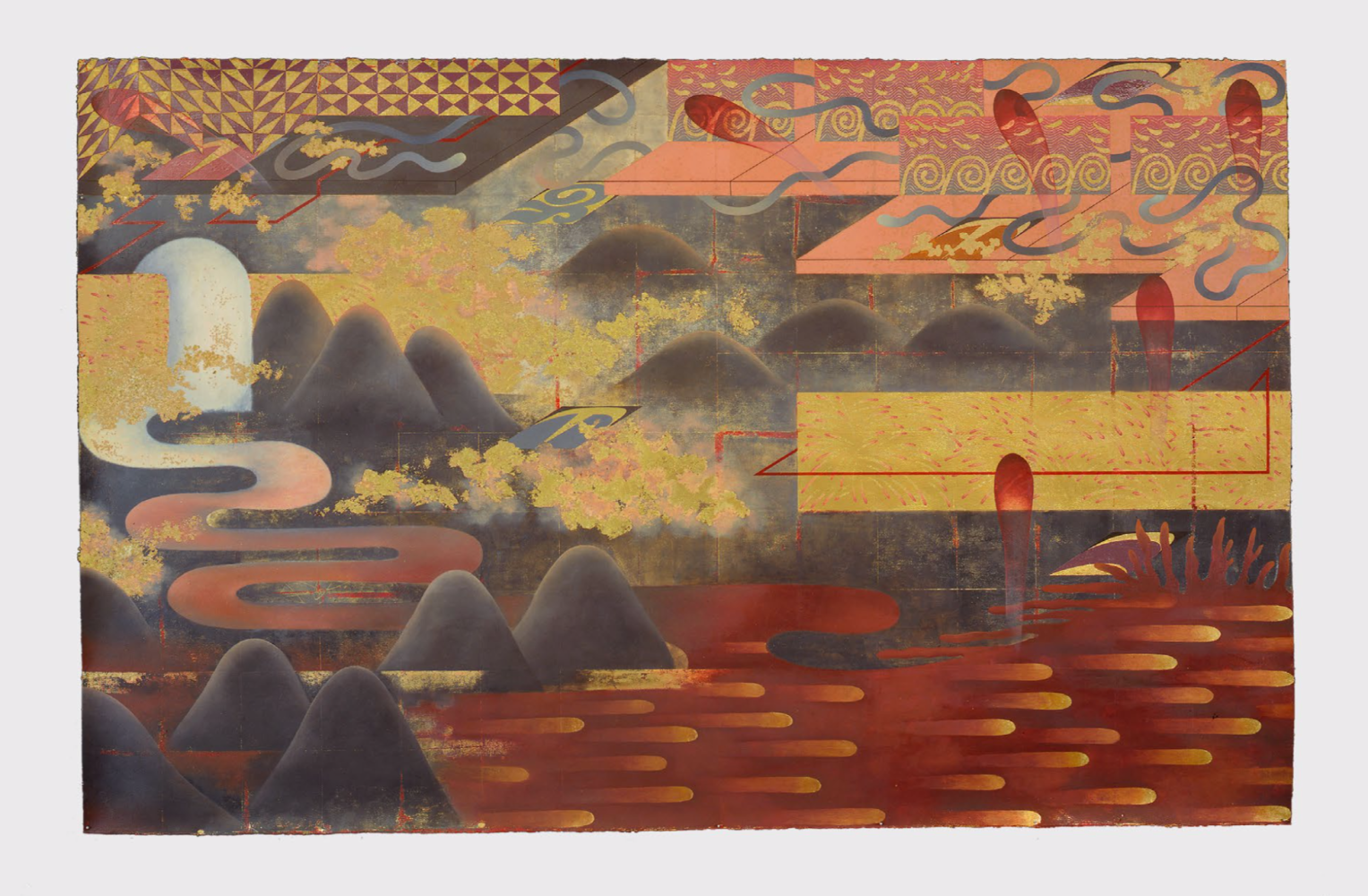

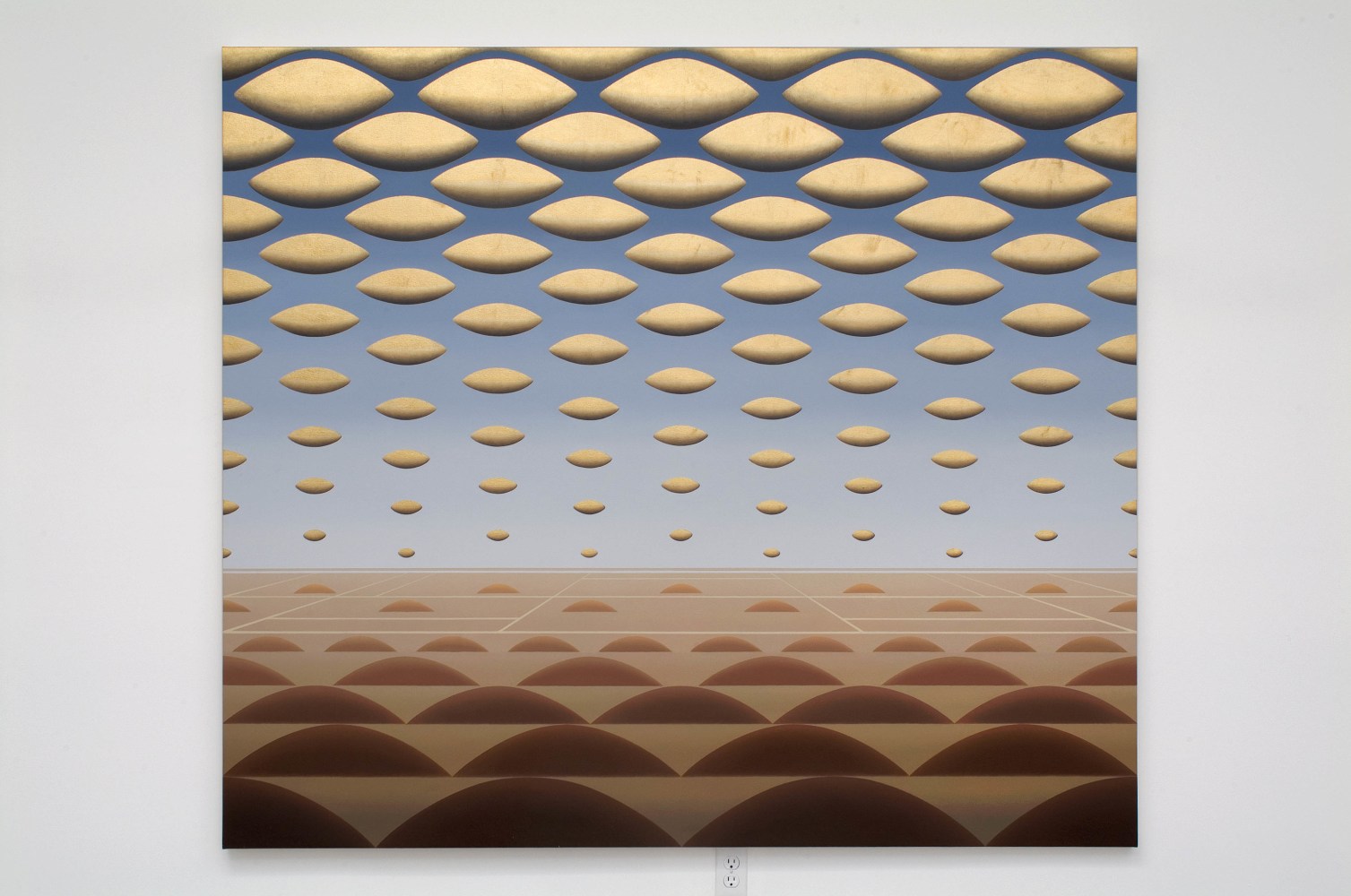

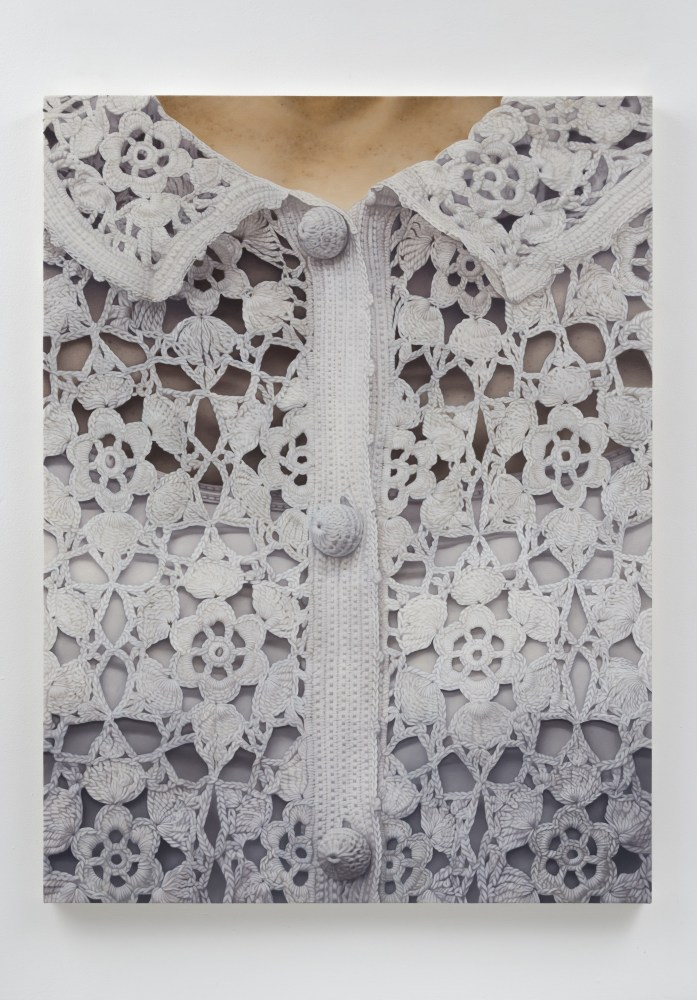

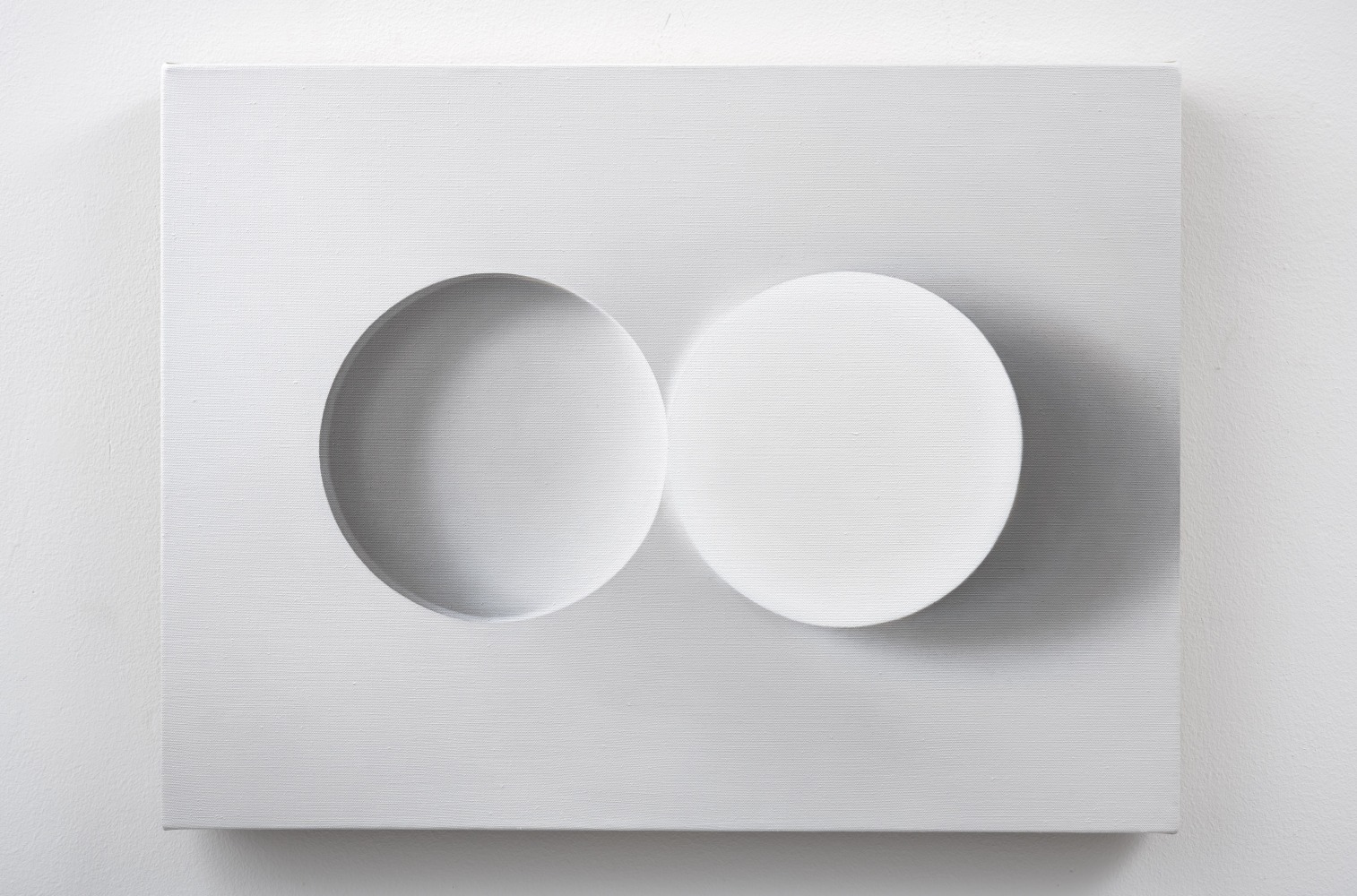

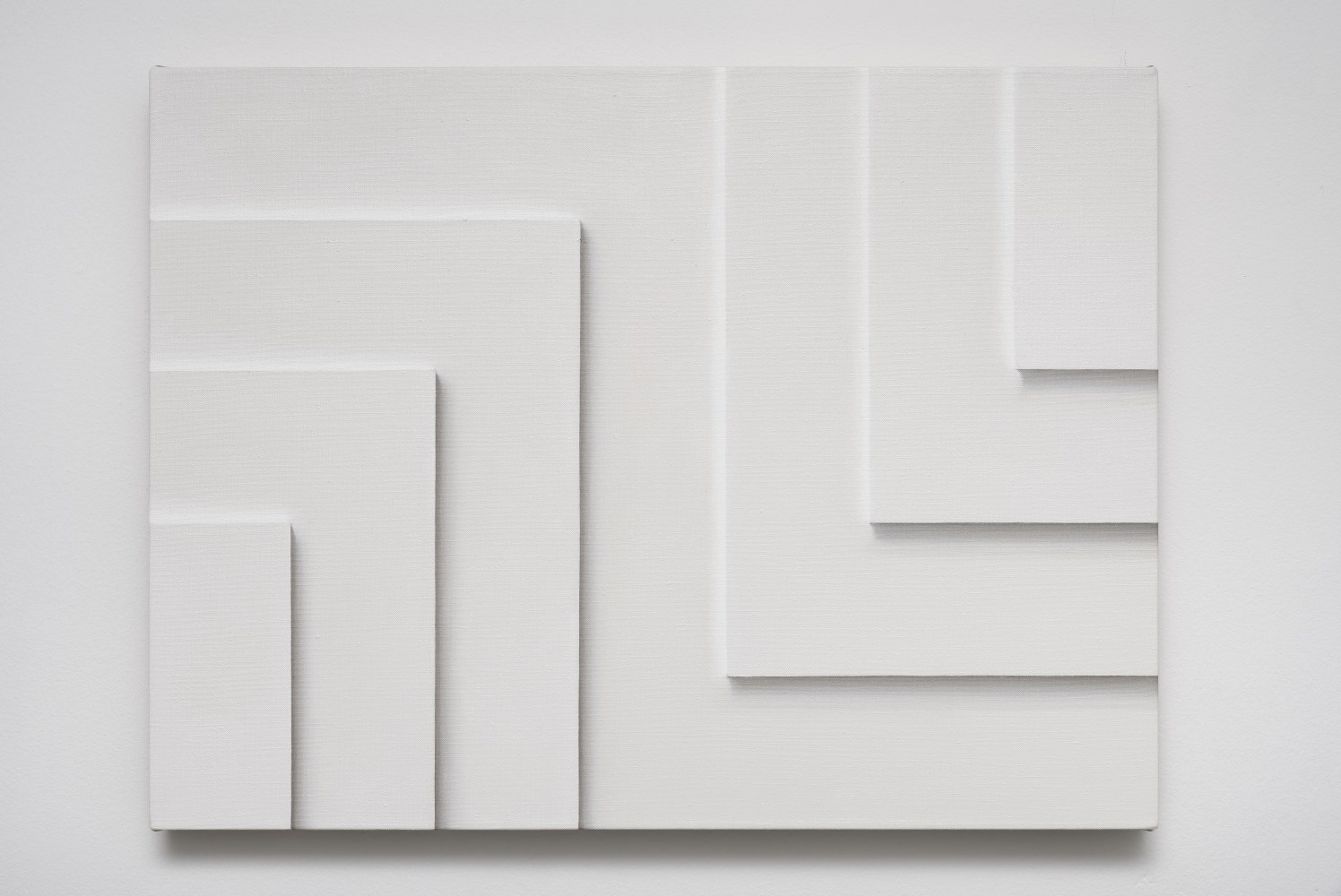

At the turn of the millennium Yamaguchi revisited her aesthetic roots, producing a series of paintings that channel her own Japanese heritage into elaborate seascapes that also call to mind the heroic achievements of 19th-century European Romanticism. The paintings begin in an aleatoric spill of metallic paint which the artist then wrestles into submission by superimposing entangled ocean, cloud and landscape, themselves set into tension with geometric patterns alternating between crisp, bright colors and reflective bronze leaf, these multiple elements resolved finally in a “dialectic of order and chaos.” Somewhat related, but rather more restrained in affect, is the subsequent series of landscapes and seascapes she describes as “abstractions in reverse” as they attempt to reverse the history of art, moving backwards in time from pure abstraction toward naturalism, pausing to capture a moment of “semi-abstraction” somewhere along the way. And then, as if resisting the stabilization of her own aesthetic language, in the 2010s she embarked on an extended, unexpected exploration of realism. A series of hyper-generic female nudes somewhat loosely based on the photographs of Alfred Stieglitz and others in his circle was followed by a group of closely cropped self-portraits featuring the artist’s own garments, which was then followed by a series of trompe l’oeil renderings of shallow white bas-relief constructions that slyly problematize the familiar distinctions between abstraction and representation.

Takako Yamaguchi (b. 1952, Okayama, Japan) lives and works in Los Angeles, California. She received a BA from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine in 1975 and a MFA from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 1978. She has held solo exhibitions at as-is.la, Los Angeles (2024, 2022); Ortuzar Projects, New York (2023); Ramiken Crucible, New York (2021); Egan and Rosen, New York (2021); STARS Gallery, Los Angeles (2021); Cardwell Jimmerson Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2010); Nevada Museum, Reno (2007); Kathryn Markel Fine Arts (2007); and Jan Baum Gallery, Los Angeles (2006). She has been included in institutional surveys including Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, Whitney Musuem of American Art, New York (2024); Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2024); The Ocean, Bergen Kunsthall, Norway (2021); With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York (2019-2021); Transcendence: Abstraction & Symbolism in the American West, Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Logan, Utah (2015); California Echoes: Women Inspired by Nature, Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, California (2007); and L.A. Post-Cool, Museum of Art, San Jose, California (2002). She is the recipient of an Anonymous Was A Woman Award (2024). Her work is in the collections of Musée d'Art Moderne Paris; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Nevada Museum, Reno; Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art; Long Beach Museum of Art, California; Eli Broad Family Foundation, Los Angeles; the Lynda and Stuart Resnick Collection, Los Angeles; and Deutsche Bank, New York, among others.

Takako Yamaguchi, Magnificat #4, 1984

Takako Yamaguchi, Innocent Bystander #5, 1988

Takako Yamaguchi, Radial Symmetry, 1990

Takako Yamaguchi, Victoria & Whiskey, 1995

Takako Yamaguchi, Sofie and Muffin, 1995

Takako Yamaguchi, Untitled, 1999

Takako Yamaguchi, Found, Lost and Then Found Again, 2004

Takako Yamaguchi, Reunion with Reality, 2008

Takako Yamaguchi, Untitled (Crochet Top), 2012-17

Takako Yamaguchi, Untitled (23), 2020

Takako Yamaguchi, Untitled (23), 2020

Takako Yamaguchi, Untitled (24), 2020